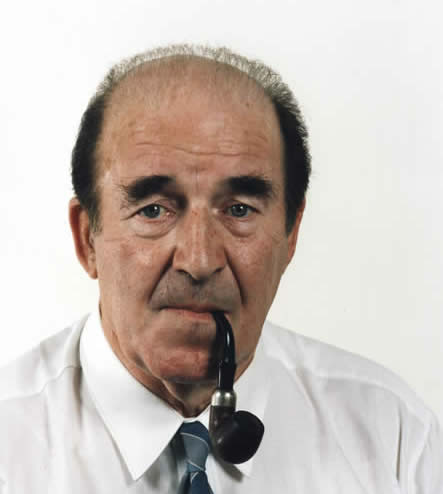

Regular readers of this blog will know to expect tributes to the most unlikely people, but I would hazard a guess that the late Neil Blaney will raise a few eyebrows. I should explain at the outset that I’m not going to deal mainly with Neil’s consistently strong line on the national question, which by itself marks him out as almost unique among southern politicos, but with Neil’s standing as one of the supreme technical adepts of Irish electoral politics.

Not many people bother to read The Donegal Mafia, which is a pity, not only because it’s one of the very few attempts – possibly the first, if I’m not mistaken – to use rigorous sociological categories to analyse Irish politics, but because it provides a snapshot of the Blaney machine – the organisation crafted by old Neil in the ’30s and ’40s, and honed to perfection by Neil Óg in the ’50s and ’60s – in its pomp, when still part of the national Fianna Fáil party. This was, at its peak, a political machine that makes Bertie’s operation in Dublin Central look almost dilettantish. This was why the national party put Neil in charge of running by-election campaigns, which he did with military efficiency and an enviable record of success – Fianna Fáilers of a certain vintage will still recall the Donegal activists with awe. I never got to see the Blaneyites in operation at that time, but even in later years their independent organisation (Provisional Fianna Fáil) was deeply impressive.

The survival of an independent organisation for over 30 years is itself something of a testament to the machine. Aontacht Éireann was a failure, probably inevitably and for a number of reasons, but it was almost as if AÉ had managed to root itself locally and survive in Donegal. You could put that down to the local strength of republican traditions, but I think a big element was that, while Boland was a bit of a loner and always prone to taking stands on his personal honour, Blaney was not only a disciplinarian but also a disciplined party man. Kevin would often recount with exasperation how Neil wouldn’t take any decision without first getting the go-ahead from the Delphic Oracle, alias the North-East Donegal Comhairle Dáilcheanntair.

This sort of cohesion probably accounts for how the clientelist system developed up in Donegal. You often hear Fine Gael technocrats complaining about how TDs have no time for legislation because they’re tied up with running clinics to deal with the trivial complaints of the great unwashed. Believe it or not, that was sorted out in Donegal, as a pragmatic reaction to Neil (after his appointment to cabinet) spending much of his time in Dublin. Decades before dual mandate legislation was ever heard of, there was a division of labour with Neil holding the Dáil seat and his younger brother Harry sitting as his personal plenipotentiary on the county council. But the division of labour went beyond that – such was the discipline, cohesion and strict hierarchy of the machine that constituents would prioritise their complaints. For a trivial complaint, like the proverbial leaking roof, you wouldn’t bother Neil but would take your case to a councillor or party activist. Neil would be held in reserve for the big problems, the ones only Neil could solve.

At root, though, the secret of the Blaney machine lay not in Neil’s technical proficiency as a politician, great though that was, but in the political spirit animating his soldiers. For the Blaneyites, who would take part in elections in Derry as easily as in Donegal, politics never ceased to be a national crusade. And there’s a lesson here – political parties are voluntary organisations, and no matter how draconian the regime the worst penalty you can inflict on someone is to tell them they can’t come to meetings or pay dues any more. A really effective machine comes into being where the men and women at the grass roots are inspired to follow a great political cause. People who think that electoral success is an end in itself can’t really comprehend the mindset that sees it as a mere by-product of a bigger struggle.

WorldbyStorm said,

August 4, 2007 at 11:45 pm

Blaney was quite a guy, although am I wrong IIRC that he was no social progressive? It was sad to see the seat fold up into FF.

splinteredsunrise said,

August 5, 2007 at 3:05 pm

No he wasn’t, not any more so than, well, most people in rural Donegal. The Blaneyites would definitely have been social conservatives, but very tough republicans and quite impressive in their way. And it’s a bit of a comedown to read the Donegal Democrat and see young Niall bigging up all the great things FF is doing.

Ed Hayes said,

August 7, 2007 at 4:17 pm

I had a discussion some years ago with some SF supporters who were all confident that as soon as Blaney died that they would take his seat. I made up a theory on the spot that the Blaneyite vote was not a republican one and would not neccesarily go to SF. Blaney may have had good points, though I am struggling to think of them (denouncing civil rights in 1969? leading the red scare in that year’s election?, presiding over internment in 1957?)but he was essentially a right-wing nationalist who had the courage of his convictions in 1970 when CJH played clever. Remember Blaney opposing divorce in 86 as well.

Why aren’t they doing tomorrow’s new dance steps the way they used to yesterday? Caoimhín Ó Beoláin contra mundum « Splintered Sunrise said,

September 5, 2007 at 11:16 am

[…] logic behind the Aontacht Éireann experiment, which ended in failure, notwithstanding Blaney’s Provisional Fianna Fáil being a sort of local analogue in Donegal. The failure was probably inevitable – the new party […]

Jim Monaghan said,

February 16, 2008 at 2:01 pm

I knew Blaney slightly. he told me that the major regret he had was using his machine to put Dessie O’Malley into the Dail instead of Hilda (the widow). He was a powerful speaker. I skoke on a H-Block meeting with him in Monaghan. He was dieect and to the point. Something like “go across the border and canvass for Sands, showthem they are not alone, don’t wait for instructions etc.”

Incidentally hegot on very well with the far leftists in the technical alliance in Brussels

Ronan Gallagher said,

September 18, 2009 at 1:25 am

Blaney was first and foremost a republican. In his time, being republican did not necessarily mean you had to be a socialist or left leaning. Many republicans had conservative views, some of which would make the hair stand on the back of your head. The overriding National question was of primary concern to all and was what united them. This unified singular objective tended to cloak the various political divisions among republicans.